I write a lot about productivity tools and methods.

I’ve written about time management and project planning and habit formation and self reflection. I’ve reviewed the things that make these possible, apps and notebooks and timers and even wrote a book about my favorite form of meditation.

I left something very important out.

Something that happened in December made me realize that I’d done my readers a disservice: all this productrivia was worthless without one particular practices.

Come with me to the Coliseum in Madison, Wisconsin, just after the Harlem Globetrotters performance, where I learned this crucial and painful lesson.

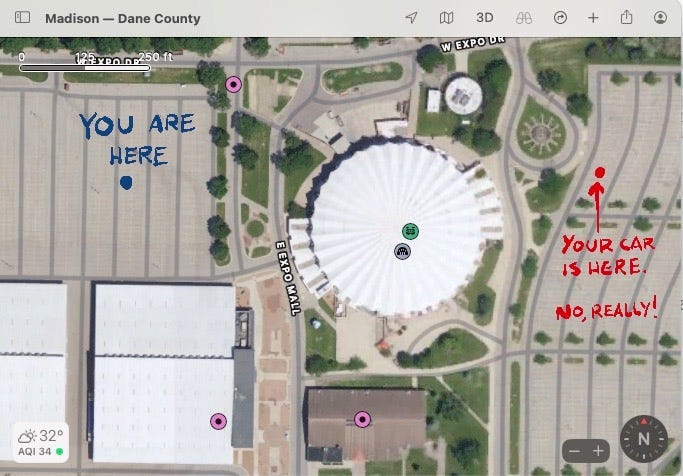

I was absolutely, 100% positive I had parked my car in this lot.

But as I stood there shivering in the Wisconsin winter, the halogen lights showed everybody else had parked their cars there, and were having no trouble finding them.

I, on the other hand, had been wandering the rows for about half an hour, trying to find it.

It was a layer cake of self-blame and physical misery. I was tired, cold, my knees hurt. But worse, I was ashamed: I was supposed to be giving my sister the dance teacher and my 6-year old nephew a ride home after their triumphant halftime performance with her dance class.

I had gotten to be Good Big Brother and Cool Uncle, because she’d been injured by a horse (yes, she also works at a ranch) and so I’d offered to be the chauffeur.

Except now I was the chauffeur who’d lost the car.

I knew that she was waiting as patiently as she could, but I also knew that my nephew was getting really tired and they both needed to get home. I was letting them down.

Worse, this situation was all too familiar. I’m notorious for forgetting where I park; once in college I’d wandered with my best friend through a parking ramp for an hour, trying to find the right stall, only to suddenly stop, look at her, and admit: “I think we’re in the wrong ramp.”

She’s not my best friend any more.

The thing is, I have an iPhone.

One of the features of the Maps app is that, when you park your car, it drops a pin. This is where you parked! it says helpfully. I’d looked at it, seen the little blue dot that was me on the north side of the Coliseum and had a little walking-trail laid out to the east side, where it said my car was.

I didn’t believe it. I’d been careful at the end of the game to make sure we’d retraced our steps, and I was completely positive that I was in the right parking lot.

But my car wasn’t there.

Priorities: I called my daughter, who’d also been at the game, and she first drove me around the lot a couple of times, on the off chance I was having some ADHD-related blindness towards my car.

Nope; it just wasn’t there. I got out and asked her to pick up my sister and nephew, still waiting at the Coliseum exit, so that at least they’d be ok. I resigned myself to the frigid hellscape of the parking lot, wandering among the few cars that were left, getting ready to call the police and report my invaluable 2014 Prius as stolen.

You know how the story ends, I suspect.

A few seconds after my daughter went to get my sister, she called me. “Dad, your car is over in the East lot. I’m looking at it right now.”

Right where my iPhone had said it was. The Maps app told me I could have walked there in two minutes.

You have to trust the tool.

I had billions of dollars in Apple R&D and the support of hundreds of high-tech global positioning satellites literally at my fingertips, all trying to tell me where I’d parked my %$#@ car…and I thought no, I’m sure I’m smarter than that.

Before you decide a tool doesn’t work for you, it’s worth asking yourself: am I letting it? The effectiveness of any system is only as good as your willingness to trust it to work.

A system only works if you work the system.