Image created by Dall-E using prompt: “an illustration of a professional with ADHD learning to adjust their time, energy and attention to be more productive.”

Click on the transcript tab for the entire podcast - and here is an excerpt that came straight from my notes:

Think about your morning commute.

Think about how many signs you rely on — street signs, construction notifications, speed limits.

And how many signals — seeing when to stop, when to go, when people are going to change lanes. In fact, think about how irritating it is when someone cuts in front of you without signaling. How that puts you on edge, spikes your cortisol, makes your heart beat faster with fear masked as anger (because it’s not that you’re mad abut the signal, you’re mad because of what could have happened if you weren’t a good enough driver to have noticed them moving over).

Now that you’ve imagined that, imagine that you have a certain kind of mental disability that made you blind to all the signs and signals.

You could see everything still. You could drive, you had the skills, but you had to make your best guess about where to turn. You had to be hyper-vigilant while driving, because you never knew when someone was going to slow down, turn, or when traffic might get faster or slower. You had to deal with other drivers honking angrily or shaking their head at you as you try to drive as well as they do — but the thing is, they can see the signs, they can read the signals, it’s second nature to them.

Why don’t you just try to drive better?

Welcome to the world of a time-blind professional with ADHD. Except instead of making the commute to work, we’re traveling through time — all in the same direction as our coworkers, both neurotypical and neurodivergent.

But very much not at the same rate. We’ll talk about that later.

To carry the metaphor a bit further, if you were blind to the signals that had been created for people that could see them but still had to get places, you would likely find other ways to help you travel. If you can’t rely on your senses, you’d use other sensors that you could rely on — perhaps the odometer telling you distance, combined with a map of the area. Maybe you’d spend extra time driving around, trying to connect landmarks to your common destinations.

And if there was a new destination, or a new route you had to take, you’d simply buckle down and accept that getting to where you need to be was going to be a bit more complex for you than for most of your colleagues.

That’s the difference — a professional finds scheduling tools useful. For a professional with ADHD, they are necessary.

Most people have a general idea of what they are going to do during their day. Most people can tell when a certain amount of time has passed, and they need to move on to something else.

That’s not how it works for the professional with ADHD. Put them in a room where there’s nothing to do, and after a bit ask them how long they think they’ve been there.

Forever.

On the other hand, put them in a room with something they care about, they are interested in, they enjoy doing, and leave them there for three or four hours. Then come in and tell them it’s time to leave.

What, already?

I know, I know. “That happens to everybody.” Yes, of course it does — it just happens to people with ADHD more. A lot more. In fact, for some, it feels like all the time.

There is no such concept of “a while”, “a bit”, or that nefarious prankster, “just a few”.

There is now. And there is not now.

Anything else? We have to rely on externalized systems.

Externalized Systems Help Everybody

Externalized scheduling tools are not new. You may remember some kerfluffle about a particular Mayan version of google calendar a few years back? Or maybe that bunch of rocks in England that line up with uncanny precision during certain times of the year.

Of course, we can’t all carry around big seasonal stone alarm clocks, or even tiny sundials on our wrists a la Fred Flintstones. If you’re reading this, you probably use the default 12-month, 365-day, 24-hour timekeeping system that we inherited from the Romans who stole it from the Greeks who inherited it from the Egyptians and Babylonians…look, it’s complicated, and outside the scope of this article.

But there’s a neat little theme to the history of how we arrived at the units we use to measure time, and it’s a pretty simple one:

It was convenient.

What follows is some “facts” about the history of time, as much as lightly-researched reputable-publications can relate them. Any errors are likely my own, but I didn’t have time for a deep dive.

But get this:

We have 60 seconds in the day and 60 seconds in the hour because that’s how the Sumerians did it. No one knows why they chose that number — best guess is that it’s usefully divisible by 10, 12, 15, 20, and 30 — but that’s how they did it, and the Babylonians learned it that way, and so did the Egyptians, and therefore the Greeks did it that way, and the Romans…all the way to that “:59” on your technologically advanced supercomputer on your wrist.

We have 12 hours in the day possibly because there are 12 lunar cycles in the year, but also possibly because you have twelve knuckles on your fingers — which you can count with your thumb like a little counting rod. Yes, seriously, that’s one of the reasons historians think the Egyptians used base 12. As digits go, it is pretty handy…

Because they liked base 12, when they invented the first sundials, they attempted to divide the day and the night into 12 sections as well — 10 regular “hours” and then an hour on each end for twilight and dawn. Unfortunately, sundials are entirely solar powered, and that made it hard to divide the night equally — so that’s when they got really complicated:

Stay with me here: Egyptian astronomers divided the sky into equal parts using 36 stars, 18 of which would appear on any given night (with each of the two twilight periods highlighted by three particularly bright stars that they could still see). That left 12 stars to divide the “dark” hours equally (yay, back to the comforting duodecimal system!).

If that seems too complex, they felt that way too. During the “New Kingdom” (well, new to them, it was in 1550 B.C.) they “simplified” it to 24 stars — still with 12 to mark the passage of the night.

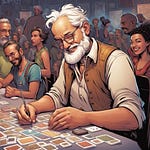

Before you get too comfortable with the idea of these twenty four hours days, you should know that since they were measured with sundials, they only were equal hours on the equinoxes. The rest of the year, the length of the “hour” varied based on the season. Roman hours, for example, were more like this:

Illustration By Darekk2 via Wikipedia — Own work, used under CC BY-SA 4.0

It wasn’t that they couldn’t divide the hours equally — there was a device called the clepsydra or water clock that kept incredibly accurate time, and that’s been found in places dated as early as 1400 B.C. It just wasn’t very useful. People’s lives were ruled by the seasons, and why pretend like a winter night was the same as a summer one, when it was obviouslydifferent?

Even when a Greek smart guy named Hipparchus finally standardized equal hours, they were more an oddity or a scientific tool than any part of everyday life. It was another 1500 years before the common people started even using hours in clocks — and another two hundred before any regular folks bothered with minutes.

We know exactly when we all finally started using the same “standard” time — December 1st, 1847. And not because that has any particular kind of galactic or seasonal or even religious significance (except perhaps to trainspotters). No, that was just the point at which the British railways adopted a standard time to measure when their trains would arrive.

The U.S. would take almost another forty years to adopt the same system, and it eventually spread throughout the world as countries had more global contact.

So what it comes down to is that this system of time that we use, that is held up as being “the most valuable asset” and “not to be wasted” and “every minute counts” — is a big pile of convenience, coincidence, tradition, and we’ve all agreed on it for less than 200 years.

That’s 6,311,433,600 Seconds, if you’re counting.

Share this post